The reality of outpatient dialysis was considered a ‘miracle’, but almost immediately dialysis became a resource so scarce that not everyone who needed it could get it. A seven-person Admissions and Policy Committee was formed to decide who would get access to the lifesaving care, and the Committee adhered to a strict set of criteria.

Dr. Belding Scribner, whose shunt made ongoing dialysis possible, deeply disagreed with the Committee’s determination not to accept local high school student Caroline Helm for treatment because she was under the age of 18 and her kidney disease was the result of Lupus.

Despite the committee’s decision, Dr. Scribner was committed to finding a solution for Caroline and patients in similar situations.

He contacted a group of his colleagues at the University of Washington and asked for their help. He wanted to build a dialysis unit small enough that it could fit into a patient’s home and be operated by a lay person. They agreed and work began on the ‘unofficial and unfunded’ project.

About four months later, near the time it was estimated that Caroline would need to start dialysis, the first home dialysis machine was ready to go. Dubbed the “mini monster”, it was a smaller version of the dialysis machine at the Kidney Center, which was called “the monster.”

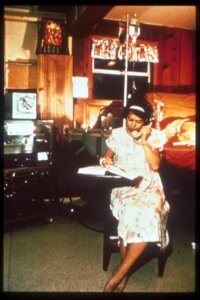

Kidney Center staff taught Caroline’s mother Susan Vukich, about dialysis and use of the machine, and with her support, Caroline Helm became the world’s first home dialysis patient.

Watch Susan Vukich, Caroline Helm’s mother, talk about their experiences.

Caroline’s story is included in NPR’s This American Life: The God Committee.